Intro from Lee Ziesche, Grassroots Coordinator and post from Claudia Campero, Mexico Organizer:

Below is a post from Claudia Campero, an organizer living in Mexico City. Mexico is at stage many countries were in just several years ago. The government is looking to open the country up to fracking and the multi-national oil and gas companies are ready to swoop in, while a majority of the population doesn’t even know what fracking is, let alone its dangerous consequences.

It’s a tough spot to be in as an organizer. But the organizers in Mexico are not alone. Just as the organizers in the UK, Canada and Romania are not alone.

This is a global movement for a lot of reasons. For one, fracking anywhere means more methane escaping into the atmosphere, increasing global warming and threatening us all. We can kick fracking out of our own backyards, but still lose everything we love to climate change if we don’t ban it everywhere.

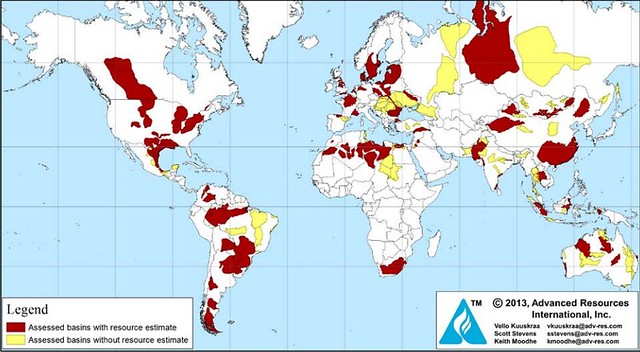

From the Energy Information Administration:Shale Gas and Shale Oil Basins the World

But I don’t think its’s an impending sense of doom that unites us. It’s the vision of what we can have instead.

The choices we make on how we’ll get our energy will impact the entire globe. If the impacts are global, it only makes sense to me that the solutions are too.

Energy “Reform” in Mexico Will Only Pave the Road for Fracking

In Mexico, as in many countries, information on amounts of recoverable shale gas reserves is uncertain. In 2011, the U.S. Energy Information Administration placed Mexico in fourth place worldwide. In 2013, we slipped to sixth place. Pemex, the Mexican state petroleum company, estimates the quantity to be even more modest. Regardless of how much gas lies beneath our feet, the consequences of the ambitious battle to frack our country is likely to be felt in many communities.

When it comes to hydrocarbon extraction, the context in Mexico is quite different from that in the U.S. In 1938, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized all oil and gas reserves. For the last few decades, Pemex has been responsible for all fossil fuel extraction in the country. This is central to the government’s income since it represents 32 percent of all federal income. Pemex is so important that it managed to escape the many reforms made to other sectors in Mexico when the country joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. However, powerful international energy corporations have been pushing for a share of Mexico’s energy resources over the last decade, and are currently already working with Pemex through service contract arrangements.

But they want much more.

Our current president, Enrique Peña Nieto, is proposing a Constitutional Reform that would allow further private participation. The main pretext for this change is that Pemex cannot develop our unconventional energy resources on its own, so Mexico needs to bring the international oil and gas corporations onboard. This reform is likely to be discussed and voted on over the following days. Although many disagree with the reform, most of the public debate is concentrated on whether or not bringing private companies to the game is in the best interest of the country.

Don’t get me wrong, this is an important debate, but it cannot be the only issue. We need a much fuller public discussion on how are we going to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and deploy truly sustainable energy solutions.

Unfortunately, even most well-informed and engaged Mexicans have not even heard about fracking, let alone your average citizen. This is a huge obstacle that we need to overcome. Many politicians are buying and selling the “abundance discourse” around shale gas and oil development without themselves knowing the full story behind the technologies that would be used to extract it.

We face yet another difficulty in Mexico: widespread violence and crime. Across the country, people face the cruel reality of robbery, kidnappings and murder on a daily basis. Environmental and human rights activists face even greater risks. In the context of impunity, violence targeting activists becomes invisible. It gets lost in the data on general violence. But we have long known that community activists who defend water, land and territory from powerful economic interest put their lives at risk to do so.

In this complex and high-stakes context, a diverse group of organizations has come together to form the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking (Alianza Mexicana contra el Fracking). We are demanding a countrywide ban on fracking. The odds are against us, but we are inspired by all the struggles around the world of those who have managed to stop fracking in many communities. As Calvin Tillman put it so eloquently in the film Gasland: “Once you know, you can’t not know.” We must put all our effort in defending our water and the future of our communities.

To learn more about what Claudia Campero and others are doing to fight fracking in Mexico visit http://nofrackingmexico.org/

Follow Us: